Wrocław (Vratislavie) n’est pas un nom facile à expliquer aux gens qui viennent de l’extérieur, pas plus que l’histoire, les émotions et les sentiments qui y sont reliés depuis des siècles.

En Pologne, il existe des villes aux noms plus « faciles » qui peuvent être compris clairement par les étrangers, aussi bien du point de vue littéral que métaphorique. Certains d’entre eux, quand on y pense, ont même un petit côté comique. Comme cette ville, située à des lieues de tout point d’eau, appelée Łódź – ce qui signifie « un bateau » ; ou encore Zakopane – qui veut dire « ce qu’on place dans un trou et qu’on enterre » – qu’on a nommée ainsi malgré le fait qu’il s’agisse d’une station balnéaire perchée bien haut dans les montagnes. Et, si on laisse de côté l’orthographe, on peut penser à Kórnik, lieu de naissance de Wisława Szymborska, récipiendaire du prix Nobel, qui pour l’oreille habituée fait automatiquement référence (phonétiquement) à kurnik – un poulailler (il n’y a pas de distinction entre le ó et le u dans l’alphabet polonais). Mais le cas de Wrocław est différent. Wrocław ne partage son nom avec rien d’autre. Il nous faut donc prendre un autre chemin pour l’expliquer.

Wrocław est la capitale de la Basse-Silésie, une région enchanteresse et quasi mystique de l’Europe centrale qui figure souvent dans les livres d’une de ses habitantes, Olga Tokarczuk, autre récipiendaire du prix Nobel. Elle a déjà écrit qu’il s’agissait d’un cosmos en soi qui aurait pu être un pays à part. La République tchèque et l’Allemagne ne sont pas très loin, et aujourd’hui Wrocław apprécie cette proximité, mais ça n’a pas toujours été le cas. Durant des centaines d’années, quand la cité est passée d’une main à l’autre, au profit de dirigeants différents, se retrouvant intégrée de façon éphémère à des empires millénaires, diverses influences, traditions et langues sont venues se mêler en son sein. Et comme bien des villes de cette région européenne, son nom a aussi changé au fil du temps, passant de versions basées sur le nom du légendaire fondateur Wratysław (« le retour de la gloire ») – Wrtaislay, Vrotislav et Vratislau, aux variantes et modifications allemandes, Wratizla, Vrezlau, Bresslaw et Breslau, qui semblent encore moins signifiantes pour les gens de l’extérieur que Wrocław.

Toutes ces métamorphoses, coupures douloureuses et discontinuités historiques (par exemple lorsqu’en 1945, la population entière de la ville est passée des mains des Allemands à celles des Polonais) rendaient difficile l’existence même d’un dénominateur commun, une constante au milieu des changements continuels. Mais Wrocław a tenté le coup et nous constatons aujourd’hui que ces efforts ont été couronnés de succès. La ville a en effet entamé un dialogue stimulant avec son passé multiculturel, avec l’aide des écrivains et des poètes qui y vivent, mené par Tadeusz Różewicz et Olga Tokarczuk. Bien des efforts ont été déployés afin de revaloriser le continuum de l’histoire et de jeter des ponts par-dessus ces ravins qui divisent artificiellement ce qui devrait être vu comme un tout organique. La ville n’a pas oublié la fumée émanant des piles de livres en feu que les nazis ont brûlés lors de la Kristallnacht – un pogrom organisé dans les quartiers juifs il y a moins de cent ans – et tente aujourd’hui de faire revivre l’esprit de tolérance, de respect et d’ouverture qui prévaut dans la rencontre de l’autre, qu’elle soit religieuse, culturelle ou linguistique. C’est peut-être là une des raisons pour laquelle une nouvelle langue a récemment fait son apparition parmi celles que parlent depuis des siècles les habitants de Wrocław… l’ukrainien.

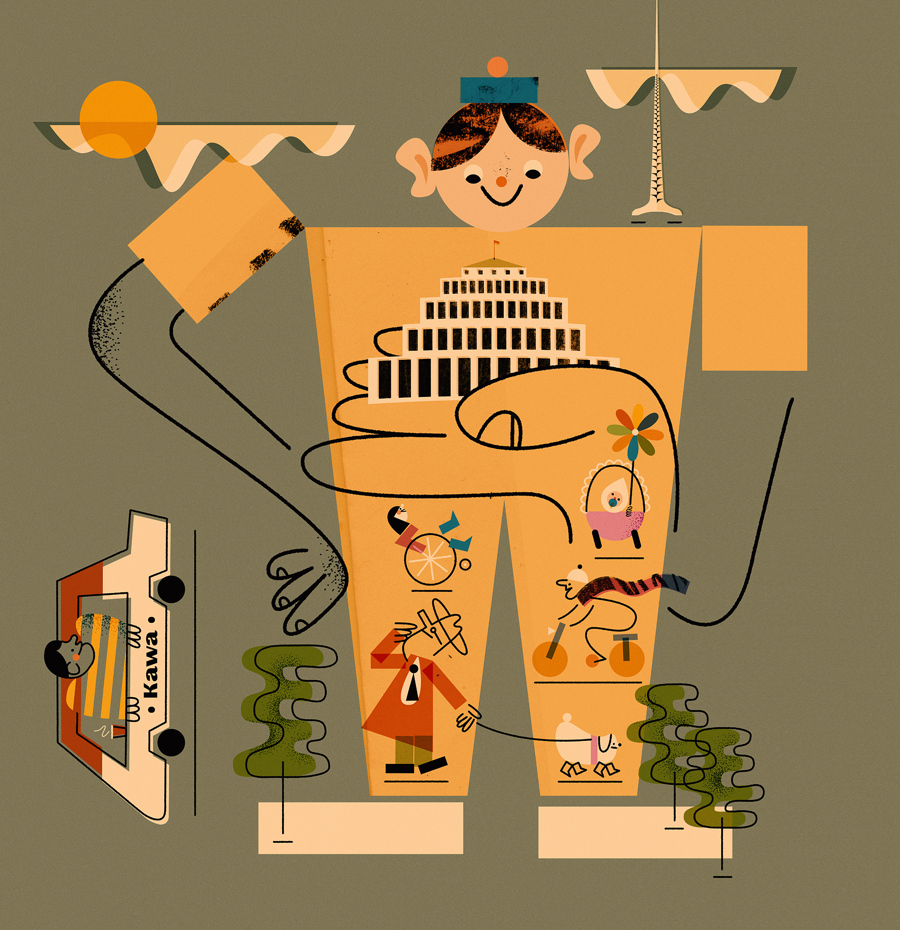

Rien de tout cela ne serait possible sans la culture, sans les créateurs et créatrices. Il nous semble par le fait même justifié de présenter la ville en insistant sur le fait que Wrocław se prononce « Wrok-Love », à l’anglaise, et qu’elle contient en elle les mots suivants : Worldliness, Respect, Ouverture, Culture, et aussi : LOVE.

Emil Pasierski

Nazwę Wrocławia dość trudno wytłumaczyć w kilku słowach osobom z zewnątrz, podobnie jak cały bagaż historii, emocji i uczuć, jakim obrosła ona na przestrzeni wieków.

Jest w Polsce kilka miast, z którymi jest łatwiej. Ich nazwy bez większego problemu dają się objaśnić obcokrajowcom, zarówno literalnie, jak i metaforycznie. Niektóre, gdy się nad tym głębiej zastanowić, mogą brzmieć nawet dość zabawnie. Mamy bowiem duże miasto Łódź – co oznacza łódź, mały statek wodny, mamy Zakopane – czyli coś, co zostało umieszczone w wykopanym dole i zasypane – niezależnie od faktu, że jest to kurort położony w wysokich górach. Abstrahując zaś nieco od ortografii, jest też Kórnik, skąd pochodzi noblistka Wisława Szymborska, który w potocznym odbiorze (na ucho) niezawodnie przywodzi na myśl kurnik, czyli wiejskie pomieszczenie dla drobiu… Z Wrocławiem już tak nie jest. Poza samym miastem nie ma ani jednej rzeczy, którą można wskazać palcem i z przekonaniem powiedzieć: „To jest właśnie Wrocław”. Trzeba więc próbować inaczej.

Miasto jest stolicą Dolnego Śląska, malowniczej i nieco mistycznej środkowoeuropejskiej krainy pojawiającej się często na kartach powieści mieszkającej tu Olgi Tokarczuk. Noblistka napisała o niej między innymi, że jest kosmosem, wystarczającym w zupełności na osobny kraj. Blisko stąd do Czech oraz Niemiec i bliskość ta widoczna jest do dziś w wielu aspektach życia współczesnego Wrocławia, choć nie zawsze stanowiła jednoznaczną zaletę. Przez setki lat, gdy miasto przechodziło z rąk do rąk różnych władców bądź znajdowało się w obrębie efemerycznych tysiącletnich imperiów, mieszały się tu rozmaite wpływy, tradycje, języki i poglądy. Jak w tylu innych przypadkach miast tego regionu Europy zmieniała się także jego nazwa, od bazujących na imieniu legendarnego założyciela grodu Wratysława (oznaczającego „powrót sławy”) form Wrtaislay, Vrotislav lub Vratislau, do germańskich wariantów i modyfikacji Wratizla, Vrezlau, Bresslaw i Breslau, które osobom z zewnątrz mówią jeszcze mniej niż słowo Wrocław.

Wśród tak wielu metamorfoz, bolesnych zerwań historii i braku jej ciągłości, gdy na przykład w roku 1945 została wymieniona cała ludność miasta z niemieckiej na polską, trudno było zachować wspólny mianownik, coś co pozostawałoby stałe mimo wszechobecnych zmian. Współczesny Wrocław jednak podjął to ryzyko i można chyba powiedzieć, że ma już na swoim koncie kilka zauważalnych sukcesów. Rozpoczął ożywiony dialog ze swoją wielokulturową przeszłością, w czym pomogli chociażby mieszkający w nim pisarze i poeci, z Tadeuszem Różewiczem i wspomnianą już Olgą Tokarczuk na czele. Wiele energii poświęcił temu, by scalić i przywrócić continuum swojej historii, przerzucając mosty nad przepaściami sztucznie dzielącymi to, co powinno być jednością. Pomny dymów wydobywających się ze stosów płonących książek i dźwięków tłuczonego szkła podczas Nocy Kryształowej sprzed niespełna stu lat, wskrzesił ducha tolerancji, szacunku i otwartości na różnorodność i wszelką odmienność – religijną, kulturową czy językową, w związku z czym zapewne tak płynnie do grona języków, którymi w przez wieki porozumiewali się wrocławianie, dołączył ostatnio także język ukraiński…

Osiągnięcie tych celów i dalsze zmierzanie ku kolejnym wyzwaniom nie byłoby możliwe bez istotnego wkładu kultury i jej twórców. Wydaje się zatem w pełni uzasadnione, by w największym skrócie powiedzieć, że Wrocław (wymawiany po angielsku jako „wroc-love”) to to słowo zawierające w sobie Światowość, Szacunek, Otwartość, Kulturę i miłości! (Worldliness, Respect, Openness, Culture and LOVE!)

Emil Pasierski

The name “Wrocław” is difficult to explain to people unfamiliar with the city, as is its history and the emotions associated with it over the centuries.

Poland has cities with “easier” names. They can be clearly explained to foreigners, both literally and metaphorically. Some of them can even be quite funny, if you think about it. The city of Łódź (“boat”) is nowhere near any body of water. Zakopane (“something which is buried”) is a resort town situated high in the mountains. Spelling aside, we have Kórnik, hometown of Nobel Prize winner Wisława Szymborska, which sounds curiously like “kurnik” (“henhouse”) because the “ó” and “u” make the same sound in Polish. But Wrocław is different; it shares its name with nothing else. So we’ll explain it in a different way.

Wrocław is the capital of Lower Silesia, a picturesque and mystical Central European region often featured in books written by Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk, who lives here. She once wrote that it is a cosmos unto itself, and could have been a separate country. Wrocław is located in southeastern Poland, near the borders of the Czech Republic and Germany. Today it appreciates this proximity, though this hasn’t always been the case. For hundreds of years, control of the city passed between rulers. Inhabitants found themselves incorporated, if only briefly, into various empires, their own identity mixing with other influences, traditions, languages and worldviews. As with many other cities in this region of Europe, its name changed over time, passing from Wrtaislay, Vrotislav and Vratislau, variants of the name of legendary founder Wratysław (“the return of glory”), to Wratizla, Vrezlau, Bresslaw and Breslau, German variants that hold even less meaning for foreigners than “Wrocław.”

All of these transitions, shifts in power and painful interruptions throughout its history (for example, in 1945 the entire city passed from German to Polish hands) made it difficult to maintain a common denominator, a constant in the midst of overwhelming change. But Wrocław gave it a shot, and its efforts have been rewarded. Led by the city’s writers and poets including Tadeusz Różewicz and Olga Tokarczuk, Wrocław opened a lively dialogue with its multicultural past. Efforts have been made to reclaim the city’s history, building bridges across chasms that artificially divide what should be a unified whole. Wrocław has not forgotten the smoke from the piles of burning books and the sound of breaking glass during Kristallnacht – a Nazi pogrom against Jews that took place less than a hundred years ago – and is attempting to revive the spirit of tolerance, respect and openness to all kinds of diversity, be it religious, cultural or linguistic. This may explain why a new language recently appeared among the many spoken for centuries by the residents of Wrocław: Ukrainian.

None of this would be possible without culture and its creators. Consequently, we would like to remind readers that Wrocław is pronounced “Wroc-love” and contains the following words: Worldliness, Respect, Openness, Culture and LOVE.

Emil Pasierski

Artistes

Emil Pasierski, auteur

Jakub Kamiński, illustrateur (Instagram)

Kasia Janusik, traductrice